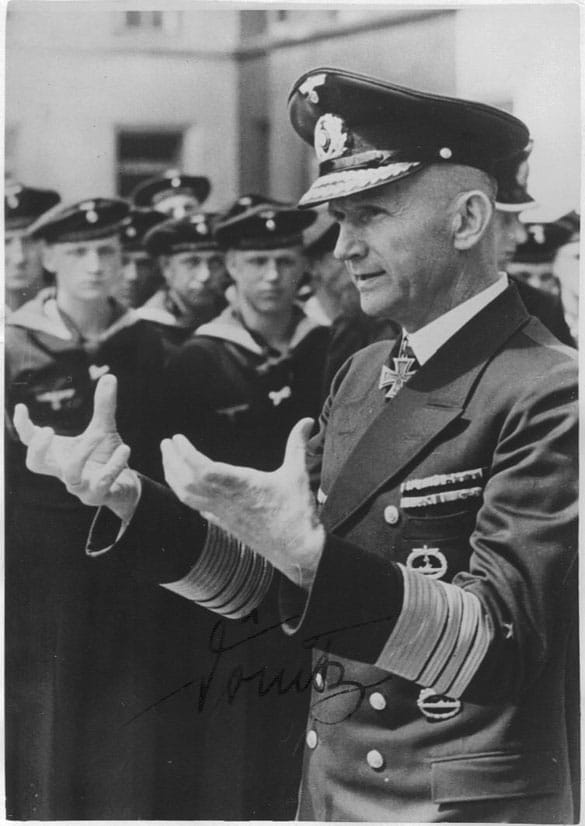

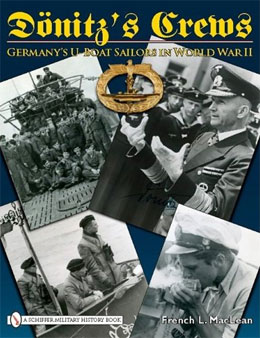

Dönitz’s Crews

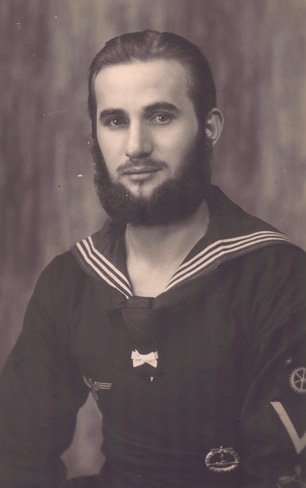

Germany’s U-Boat Sailors in World War II

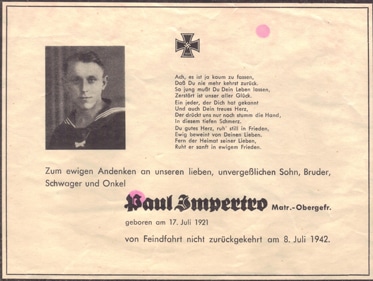

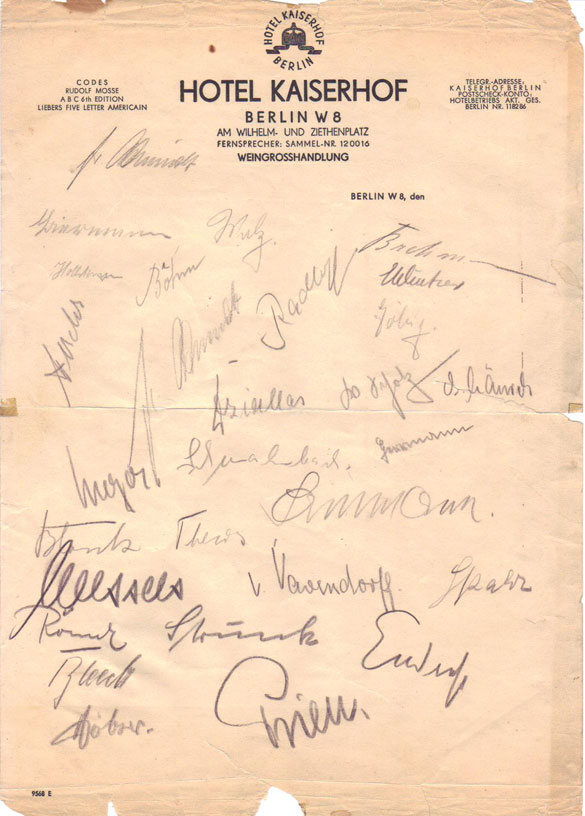

U-boats almost won the war for Germany by bringing Great Britain to its knees in 1941-1942. 40,000 U-boat sailors went out on patrol; 30,000 never came back. Günther Prien in the U-47 sinking HMS Royal Oak in Scapa Flow. U-262 that attempted a daring rescue of captured German U-boat sailors in Canada. U-200, loaded with a Brandenburg Commando, Germany’s special forces troops, trying to blow up the largest Allied drydock on the Indian Ocean. Karl Dönitz: who once had his men vote on continuing the war in 1943, when almost every boat was not returning home; how personal leadership can overcome setbacks. How the German Navy used a very low frequency radio transmitter, called Goliath, to contact U-boats under water almost anywhere in the world. And that today in Russia there is a clone of this covert equipment that can do the same thing.

U-boat skippers came in all degrees of proficiency; the best ones sank thousands of tons of enemy ships, won various grades of the Knights Cross and were often beloved by their crews. The worst ones were relieved of command, unless they first really made a critical mistake that destroyed the boat and killed the crew.

The best U-boat commanders would admit it – the commander did not know where every single pipe and cable in a U-boat was located and what its function was; they did not know how every single gauge worked or what every single valve controlled. They did not know; but their Chief Engineers did – and every sailor on every U-boat knew that next to the commander the Chief Engineer was the most important man on the boat. Engineer officers were often thought of as magicians – exorcising demons from the massive diesel engines and electric motors so the boat could make it home after a successful cruise – and as ingenious improvisers who could patch up almost any piece of equipment or fixture of broken pipe after a depth charge attack.

But everyone knew who really ran the boat – the Chief Petty Officers and the Petty Officers.

With dozens of historical documents and over 400 photographs, the author not only presents a comprehensive history of U-boat crews and the undersea war, but also shows how those with an interest in the U-boat war can find U-boat-related artifacts and how they can trace many to specific boats – and then research what those boats and crews accomplished.

Dönitz's boys were many things; they could be young, resourceful, courageous, stoic, ambitious, intelligent, confident, determined, chivalrous, tenacious and idealistic. They could also be nervous, cynical, depressed, frustrated, desperate and terrified. Sometimes they could be many of these characteristics in a single, short period, from the ultimate high of sinking an enemy ship, to moments later sitting inside a cold, wet, dark steel "coffin," during a rain of exploding depth charges. Then, they waited for the one that would destroy their boat by crushing the hull and killing them instantly or causing their boat to sink uncontrollably to the bottom of the ocean. There, they would choke to death on the toxic fumes emitted by broken batteries or – one by one – die by inches in the cold, wet darkness as their oxygen supply slowly ran out. Afraid – they all were, but in a U-boat, you couldn’t let your fear take control, or the enemy would locate you immediately.

Most boats had a small galley with two hotplates to heat meals for a crew of forty-four to fifty-six men. However, in rough seas, for safety, the hotplates were not used and the food was thus served cold. As less than a quarter of the crew could actually eat their meals at proper tables, the rest of the crew sat on the hard, damp metal floor deck plates or on boxes, precariously balancing their dish and bowl on their knees in order to eat their meals quickly before the grease and gravy cooled and coagulated. The dishwasher on a U-boat was not a machine, but one of the sailors using warm seawater from the cooling system in the engine room – without detergent – often with a rag of "questionable appearance."

Temperatures inside a U-boat varied, but none was quite comfortable, as no operational U-boats were provided with air conditioning, heating or cooling systems. In the Arctic and North Atlantic, it could be quite cold and damp, while in the Caribbean, West Africa or Mediterranean overall temperatures inside a boat could reach 95°F, with the temperature in the engine room approaching 122° F; one U-boat commander reported that in the Gulf of Aden temperatures in the engine room hit 163° F! The humid air produced a squalid, oppressive, damp, greenhouse effect – along with an eerie fog that would sometimes form around the interior lights. Sweaty men, unable to bathe, in a cramped humid environment for eight weeks or more on patrol could make the atmosphere inside of a U-boat more foul than the stale air in the dirtiest athletic equipment-storage locker in a run-down gymnasium. Eau de cologne was ever-present, and crews had a particular term for the rank foulness – "U-boat stink."

Service on a U-boat could age a man very quickly. Crewmen pulled watch four hours at a time. Four hours on the bridge of a surfaced boat, on a raging sea, in temperatures hovering at the freezing mark, occasionally in driving snow or sleet storms, could seem like an eternity. Sometimes, the frozen spray clawed the men's faces bloody as winds in the Arctic Circle, for example, sometimes exceeded one-hundred miles an hour and giant waves tried to violently rip the men off the slick bridge and carry them to the depths below. Given a different set of wartime circumstances – those that were less lethal – Dönitz's boys easily could have become Dönitz's old men. But the war did not go according to plan and most of Dönitz's boys would die as young men.

This is their story.

***

Dönitz’s Crews highlights many of the most successful German attack submarines in World War II (U-47, U-37, U-65, U-97, U-103, U-105, U-107, U-331, U-333, U-404, U-502, U-504, U-506, U-516, etc.) But there is much more. Included is the story of the U-262 that attempted a daring rescue of captured German U-boat sailors held in a prisoner of war camp in Canada. The work also details the intended mission of the U-200 and her crew that included a special demolition team from the Brandenburg Commando, Germany's special forces troops. Their mission was to disembark off South Africa and blow up the largest Allied drydock in the Indian Ocean (included photos show the team training for the mission.)

Over 400 photographs identified to crew and equipment of 47 different U-boats; U-boat militaria shown for crewmen on 34 different boats; operational histories for 46 U-boats to include detailed crew lists for 45 boats, 333 pages. (Schiffer Publishing)

Dönitz’s Crews: Germany’s U-Boat Sailors in World War II (auf Englisch, 400 Fotografien, 333 Seiten.) Deutschlands U-boot Männer im zweiten Weltkrieg. Horst Bredow, Direktor des deutschen U-Boot Museum (Cuxhaven) hat gesagt, dass dies eines der wichtigsten Bücher auf Deutsch u-Boote im zweiten Weltkrieg. Schiffer Verlag.

"Dear loved ones! Should you learn one day that our boat has not come back, there is no need for you to keep up hope. We are blessed to be able to serve under such a marvelous commanding officer. We are agreed that none of us will fall into the hands of the British. We want to fight and win together; or else, if it cannot be helped, to die together."

Comments on Dönitz's Crews

“With Dönitz’s Crews, French MacLean has captured the very essence of U-boat warfare. With his detailed text and hundreds of previously unpublished photographs, he shows the fear, adrenalin, anticipation, courage and pride of these undersea warriors. Every Submariner needs to read this book to learn from those who have gone before him; every Anti-Submarine Warfare officer must read this book to understand the deadly and tenacious nature of his foe.”

- Rear Admiral Michael Mahon United States Navy, Retired