1874 Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospection Expedition Route

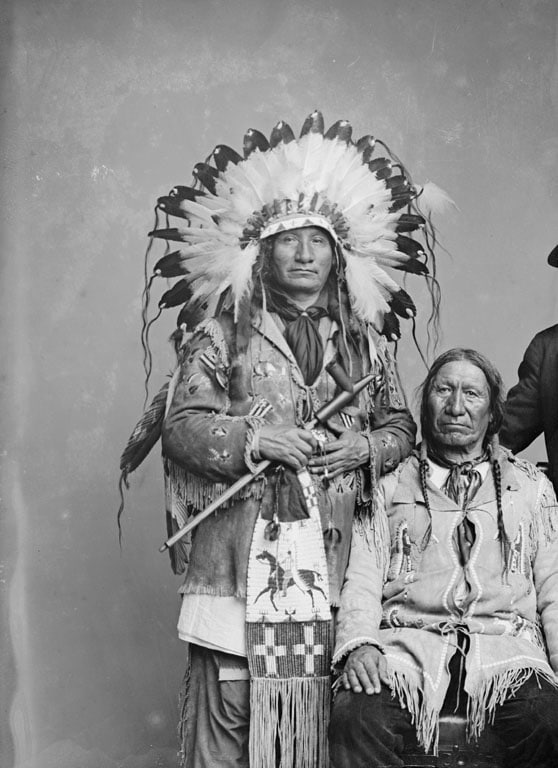

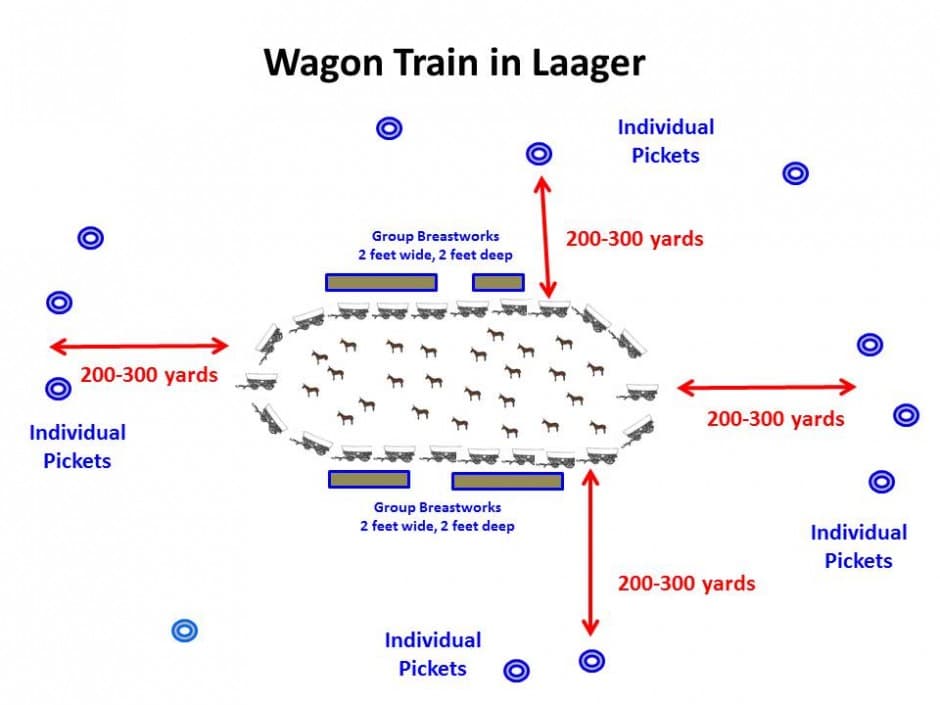

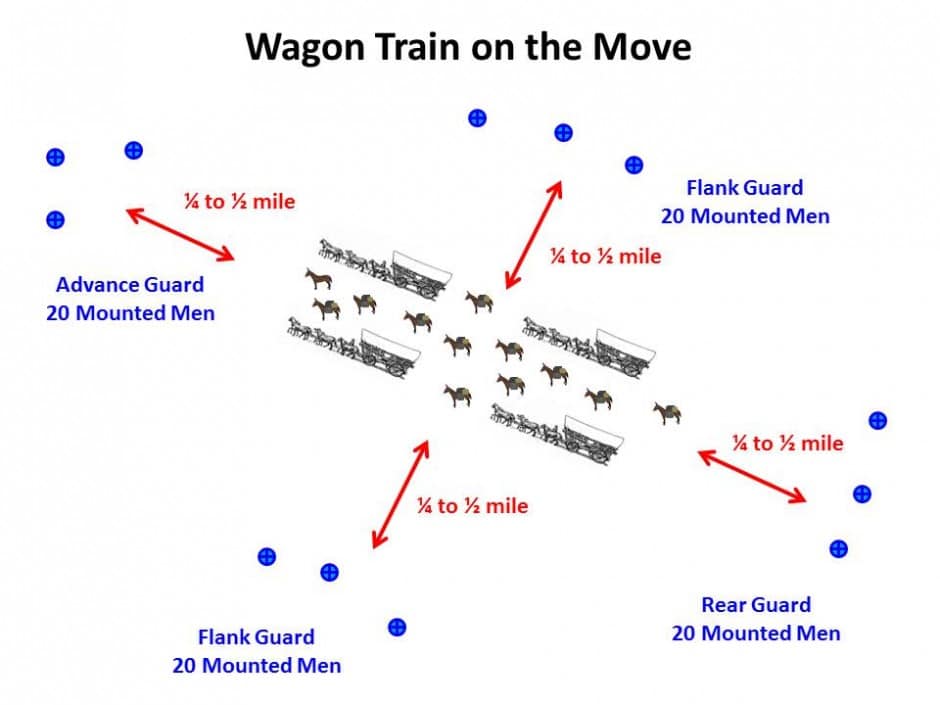

They called themselves “The Boys” and they numbered about one-hundred and fifty of the most adventurous – and cantankerous – hombres to ever ride a wagon train in the Old West. Scouts, gold prospectors, a former Texas ranger, buffalo hunters and Civil War veterans of both sides – men who counted coup at Antietam, Stones River, Nashville, Missionary Ridge, Vicksburg, Kennesaw Mountain and Atlanta – they may have been the deadliest collection of shooters to ever hit the trail west of the Mississippi River. Now, however, they were not trying to corral Confederate raider John H. Morgan or conquer “Reb” cavalry commander Jeb Stuart. “The Boys” were now up on the Great Plains, along the mighty Yellowstone River and her tributaries – waterways with fabled names Powder, Tongue, Rosebud, Big Horn, Lodge Grass and Little Bighorn. And their adversaries now were the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne – some of the greatest light cavalry to ever gallop over the North American continent. This time, it was the warriors, not the frontiersmen, doing the hunting and they were led by the formidable chieftains Hump and Inkpaduta, with perhaps Sitting Bill waiting in the wings. The experienced warriors, who learned how to ride almost before they could walk, knew the terrain and what waited around every corner. What they did not know was that “The Boys” were armed with two cannons, for which they had devised ingenious explosive canister rounds – as well as dozens of Springfield “Big Fifty” rifles and powerful Sharps buffalo guns and could drop anything on two or four legs a long, long way away. What both sides had in common was suffering through three months of a brutal Montana winter, where temperatures plummeted to thirty degrees below zero and where only the strongest survived.

Despite its obscure place in history, we are blessed with over one-hundred years of sources, if only we will search for them. Unlike the demise of George Custer some two years later at the Little Bighorn – only a few miles from where “The Boys” had fought, there were plenty of survivors to tell the story.

“It was in ‘74, and I don’t think there was ever a march made into the heart of a hostile Indian country that ever equaled it. The country was alive with Sioux Indians and yet we made that march, losing only one man out of 146. We were in search of gold. In one fight, we had the best warriors of the Sioux nation pitted against us…The prime object of the movement was to open up the Wolf Creek country, where, as the party then supposed, rich placers [alluvial deposits] could be found.”

These were the words of James Gourley, years after participating in the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition; what he did not write was that in that last battle, there may have been upwards of 1,400 warriors riding in to attack – long odds for any defense. The warriors understood this, and perhaps out of respect, “The Boys’” opponents, certainly led by Hump and Inkpaduta – and possibly in the presence of the great Sitting Bull – called them Wan-tan-yeya-pelo (straight-shooters) and Maka-ti-oti (dug-out dwellers) because the frontiersmen dug rifle pits from which they poured out round after round of accurate fire. And the warriors soon nicknamed these huge rifles the “shoot today, kill tomorrow” guns.

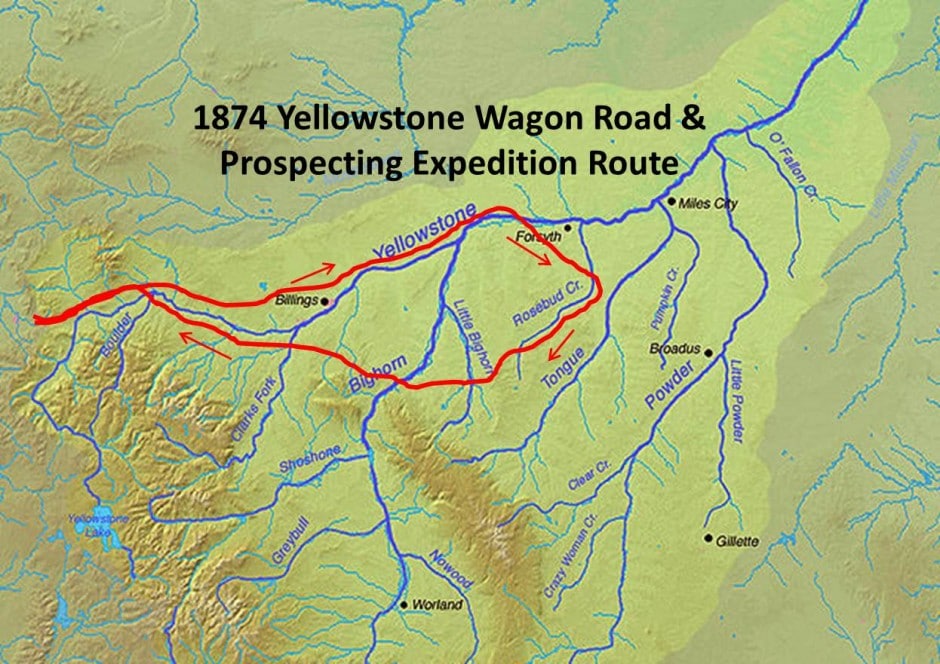

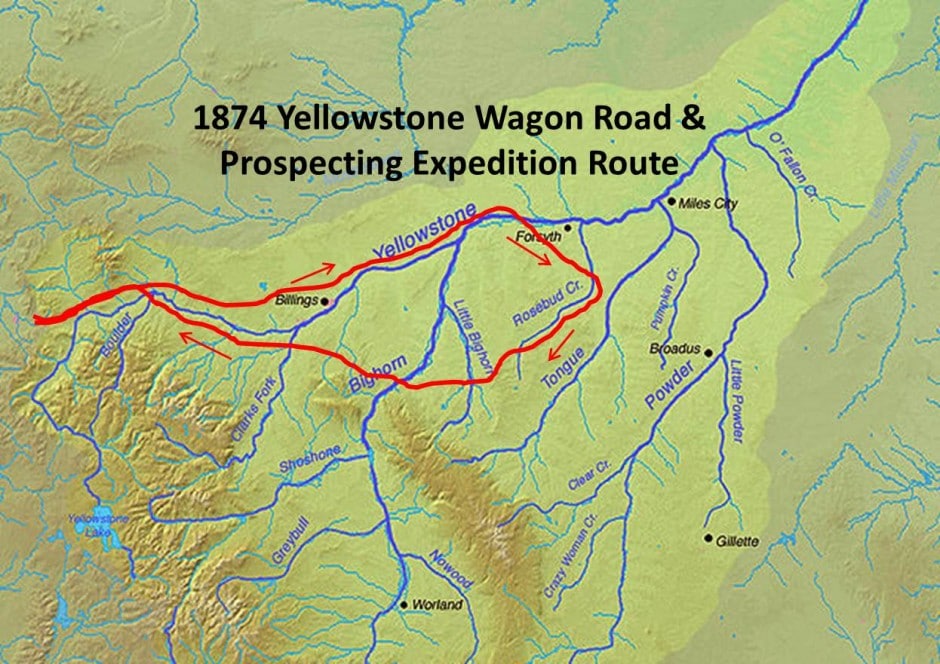

The written history of the events you are about to read is as such: In February 1874, the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition was a quasi-military operation, departing from Bozeman in the Montana Territory, and proceeding along the Yellowstone River Valley for the purpose of determining the suitability of the Yellowstone River for navigation and scouting a wagon road. Equally as important – at least to the members of the expedition – it was a search for gold. This expedition, headed by veteran Indian-fighter Frank Grounds, was supposed to travel down the Yellowstone River to the mouth of the Tongue River, but turned around at Rosebud Creek and was not able to reach its goal because bison had eaten all the grass in this area earlier in the year, but also because Grounds realized the Lakota and Cheyenne would not stop until the last man in the wagon train went down. The expedition survived, and at least six key participants of the 1874 trek played prominent roles with the United States Army at the Little Bighorn campaign two years later.

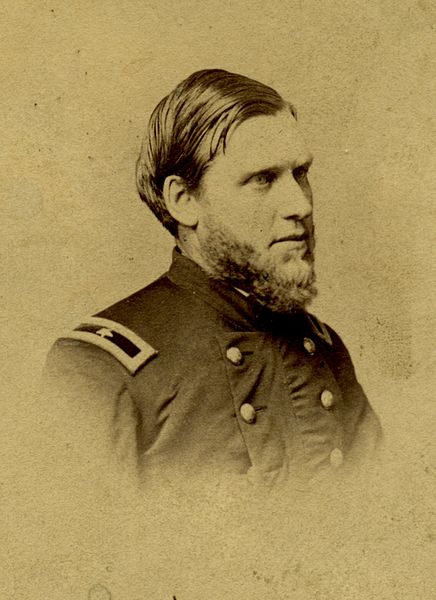

Behind the scenes is another story. The territorial governor of Montana played a significant role in the formation of the expedition, but his motivation – at least in part – may have been less than noble. And what role did the United States Army play in equipping the expedition through a cavalry major at Fort Ellis who was a Civil war hero and West Point classmate of Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, the commander of the Division of the Missouri?

But, as Napoleon once said, “What is history but a fable agreed upon?” That has never been truer than with the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition, which entered the legend that became the Wild West, almost before it made it back to Bozeman, Montana. This book seeks to cut through that legend, with a result that what really happened is actually much more incredible that what – until now – we like to believe happened. Equipped with two mysterious artillery pieces, the men of the wagon train had in their midst some of the greatest buffalo hunters of the era. One of them, Jack Bean, would fire a long-range shot at the expedition’s climactic “Battle of Lodge Grass Creek” that was the longest recorded hit against a single opponent in the history of frontier America. And who would ever believe that a former slave – and later a sergeant in an elite all-black Union unit, the only combat element of the war to serve under exclusive leadership of black officers – went hand-to-hand, with knife versus tomahawk against a Lakota warrior, vanquishing a foe that some believe may have been a son of Sitting Bull?

One could make the argument that every man on the expedition, and their Lakota and Cheyenne opponents as well, were also heroes, who defied the odds in simply surviving. Previously just listed as non-descript names in old books, with today’s resources, we can now determine exactly who many of them were, how they shaped history before and after the fight and what happened to them in their twilight years of telling old stories to their grandchildren around the hearth.

Just thirty years after the expedition, Jorge Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, better known as George Santayana, wrote that, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but what about those participants in history, who remember it incorrectly or take the wrong lessons of the past and try to apply them to different circumstances in the future? Perhaps an understanding of the 1874 Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition may also shed light on one of the West’s greatest mysteries that will never be solved – the defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. The warrior chiefs fighting the 1874 expedition, and at least six frontiersmen on the wagon train, would later play prominent roles in the 1876 Great Sioux War. How these men saw the conduct of the 1874 fighting and how they correctly or incorrectly interpreted this information to adapt to the fighting in 1876 would significantly affect the outcome of that latter conflict for better or worse.

In our collective history, the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition of 1874 has remained an obscure sidelight that has never been remembered. Even the great historian Dr. Walter S. Campbell (born Walter Stanley Vestal) wrote in 1956 that he was generally not informed about the expedition. On the other hand, the “Battle of the Little Bighorn” of 1876 remains a watershed moment that will never be forgotten. George Santayana would have understood completely.