Chełmno was a hybrid extermination camp whose mechanism for death was a special commando, Sonderkommando Lange, of mobile toxic gas vans in which the victims were killed. These vans then dumped the bodies in mass graves in a nearby forest, the Rzuchów Forest. The location, referred to by the Germans as the Vernichtungslager Kulmhof, was thirty-one miles north of the metropolitan city of Łódź, in which a large Jewish ghetto had been established by the Nazis after their invasion of Poland in 1939. Chełmno is actually a shortened named for the Polish village of Chełmno nad Nerem, named Kulmhof an der Nehr in German. It was centrally located in the German district of the Warthegau, which top-ranking Nazis wished to make “Jew-Free”, Judenrein.

Four estimates have been made over the years as to the number of victims (mainly Jews and gypsies, but also some non-Jewish Poles and even some Czechs from Lidice) who perished in the operation of the facility: 152,000; 180,000; 340,000; and 200,000. Just as the location was a combination of stationary and mobile elements for killing, so the Nazi staffing of Chełmno was a joint SS and German police; Order Police (Ordnungspolizei) and Protective Police (Schutzpolizei) operation. One man, who escaped, later wrote that Chełmno was a “human slaughterhouse.”

The stationary portion of the operation centered about the grounds of a nearby mansion – the Nazis there known as the Hauskommando; victims were brought to the village by trains and trucks. After unloading, the Jews surrendered their possessions, remaining in the mansion several hours to no more than one day before they were forced into the special gas vans and killed. During the second period of operation, after the mansion had been destroyed, a church was used to hold the victims before their deaths. The Germans at the forest piece of the operation were known as the Waldkommando.

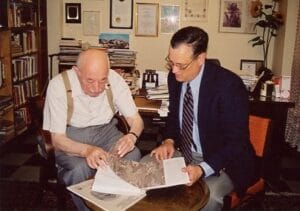

Chełmno remains one of the lesser-known and more-mysterious extermination efforts connected with the Final Solution (also known as the Final Solution of the Jewish Question (Endlösung, die Endlösung der Judenfrage), recent research – such as Chełmno and the Holocaust: The History of Hitler’s First Death Camp, by Patrick Montague has provided insights into many aspects of this terrible facility. The following individuals are believed to have been perpetrators at Chełmno during its two periods of operation:

(November 1941-April 11, 1943)

SS-Oberscharführer Basler, gas van driver

SS-Hauptscharführer Alfred Behm, transport commander; captured by the Soviets in 1945; fate unknown

(Police) Walter Bock, guard; born June 16, 1912; acquitted at trial in 1963

Polizeihauptwachtmeister Otto Böge, sergeant of the guard

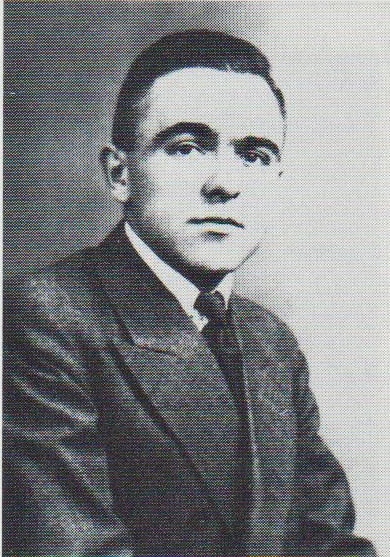

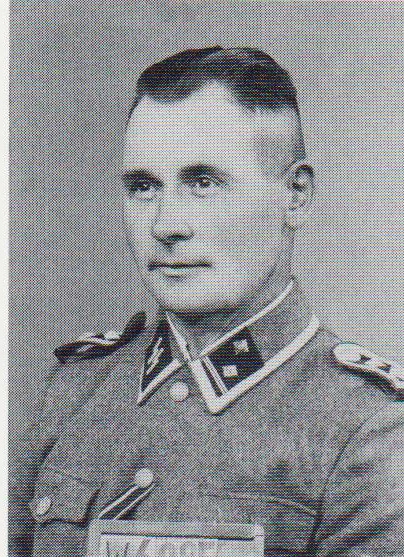

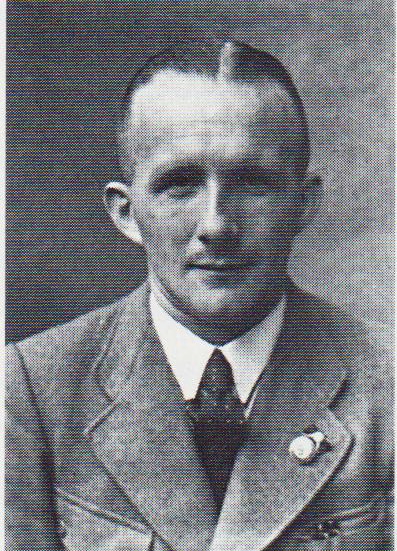

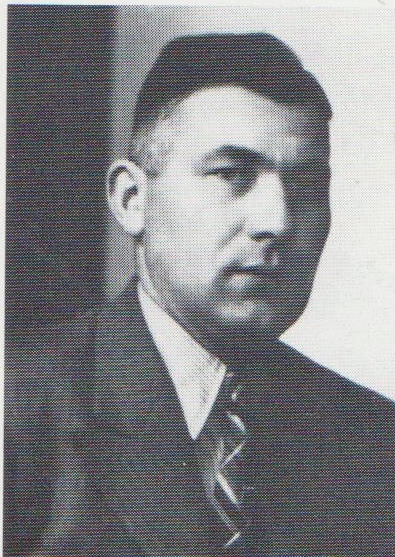

Hans Bothmann

SS-Hauptsturmführer & Kriminalkommissar Hans Bothmann, commandant; born November 11, 1911 in Dithmarschen, Germany; arrested by the British on April 4, 1946; hanged himself the same day

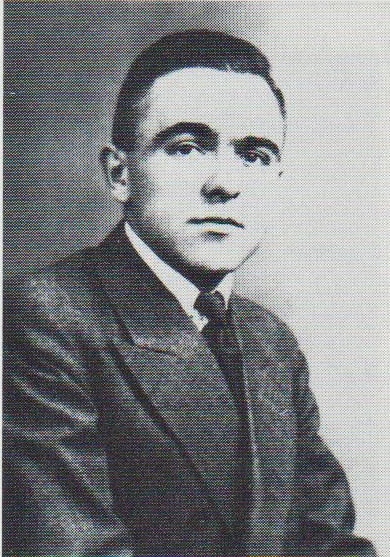

Erwin Bürstinger

SS-Hauptscharführer Erwin Bürstinger, motor pool; born February 16, 1908 in Wels, Austria; fate unknown

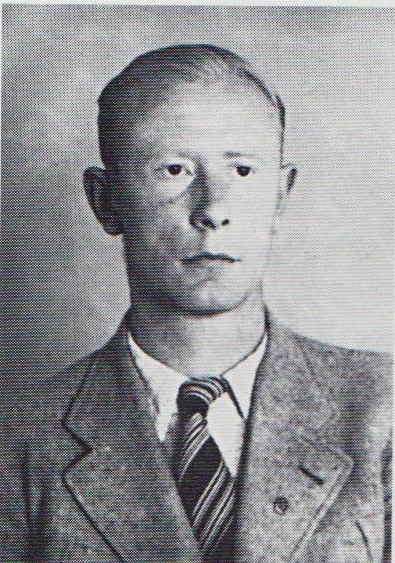

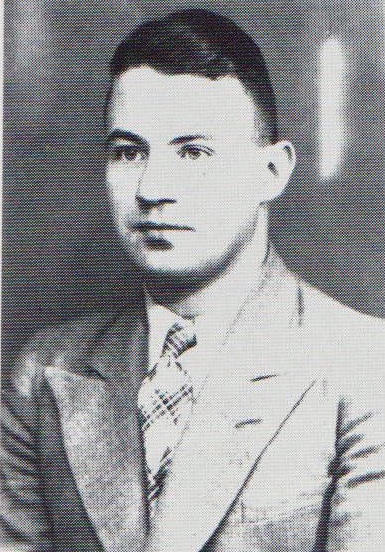

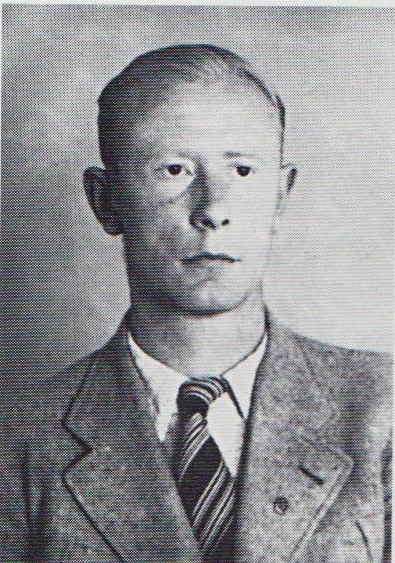

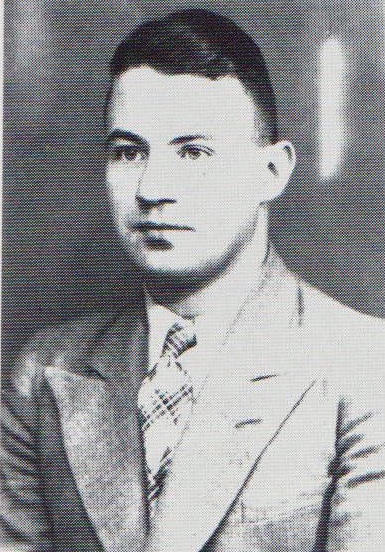

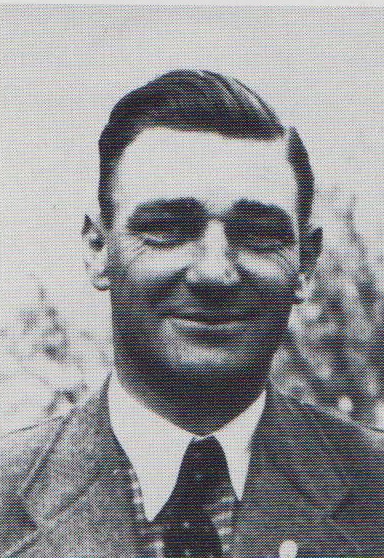

Walter Burmeister

SS-Rottenführer Walter Burmeister, commandant’s driver; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 13 years in prison

Polizeihauptwachtmeister Gustav Fiedler, sergeant of the guard, operated bone-crusher in forest; born October 23, 1910; tried in Germany in 1965 and received sentence of 13 months in prison

SS-Hauptscharführer Karl Goede, victim valuables

Wilhelm Görlich

SS-Hauptscharführer Wilhelm Görlich, administration; taken prisoner by the Soviets in February 1945; sentenced to 25 years in prison; released in 1949

Alois Häfele

Polizeimeister/Revierleutnant Alois Häfele, supervisor of Jewish labor at the mansion; born July 5, 1893 in Württemberg; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 15 years in prison; sentence reduced to 13 years on appeal

Polizeiwachtmeister Simon Haider, forest guard commander; died November 4, 1958

Polizeioberwachtmeister Karl Heinl, mansion guard commander; born April 11, 1912; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 7 years in prison

Polizeiwachtmeister Friedrich Hensen; born November 29, 1920

SS-Oberscharführer Oskar Hering, gas van driver; killed in action with the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division “Prinz Eugen” at Vratanica, Serbia on October 4, 1944

(Police) Wilhelm Heukelbach, guard; born February 28, 1911; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 13 months in prison; sentence dropped on appeal

Herbert Hiecke-Richter

SS-Oberscharführer Herbert Hiecke-Richter, transport commander; fate unknown

Revieroberwachtmeister Kurt Hoffmann, operated bone-crusher in forest

Polizeioberleutnant Gustav Hüfing, supervisor police guard; born in Wesel; died July 24, 1958

Fritz Ismer

SS-Hauptscharführer Fritz Ismer, victim valuables; served in the 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg”; no charges were ever brought against him

Erich Kretschmer

SS-Unterscharführer & Polizei-Oberwachtmeister Erich Kretschmer, transport guard commander; fate unknown

Gustav Laabs

SS-Hauptscharführer Gustav Laabs, gas van driver; born December 20, 1902; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 15 years in prison; sentence reduced to 13 years on appeal

Polizeioberleutnant Harold (Harry) Lang, supervisor police guard, fate unknown

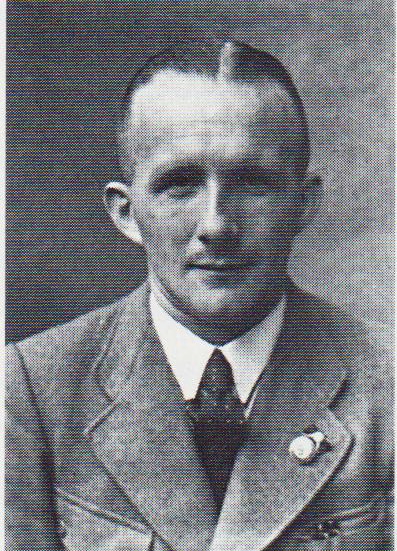

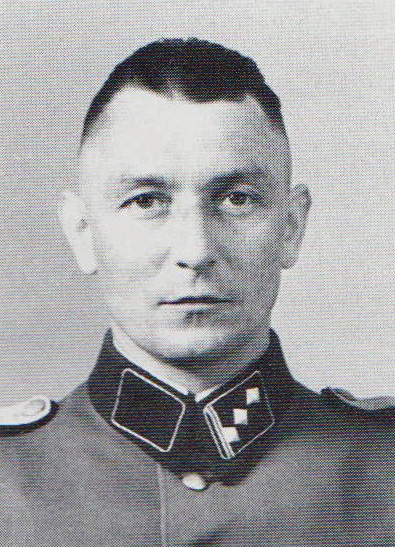

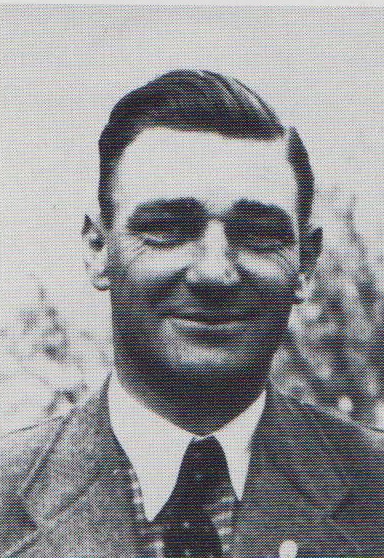

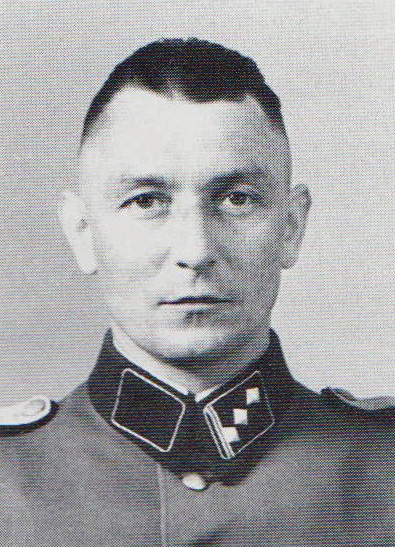

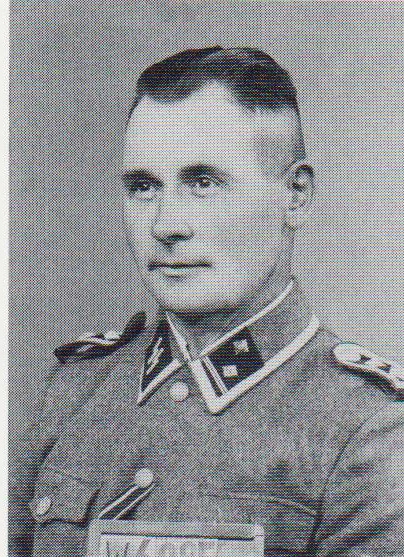

Herbert Lange

SS-Hauptsturmführer Herbert Lange, commandant; born September 29, 1909 in Menzlin, Pomerania; killed in action on April 20, 1945 at Niederbarim near Berlin

Polizeimeister Willi Lenz, supervisor forest camp; born in Silesia; ambushed and hanged by last surviving group of Jews on January 18, 1945 at the granary as the Nazis evacuated Chełmno

Polizeioberleutnant Harri Maas, supervisor police guard

(Police) Friedrich Maderholz, guard; born November 7, 1919; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 13 months in prison; sentence dropped on appeal

Polizeiwachtmeister Theodore Malzmüller, guard; served with the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division “Prinz Eugen”; provided testimony at post-war trial in Germany

(Police) Mehring, guard; born March 25, 1920; acquitted at trial in 1963

Polizeimeister Kurt Möbius, transportation at the mansion facility; born May 3, 1895; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 8 years in prison

SS-Hauptscharführer Friedrich Neumann, administration

Herbert Otto

SS-Obersturmführer Herbert Otto, deputy commandant; born October 9, 1901 in Dresden; killed in Prague, Czechoslovakia on May 6, 1945

SS-Scharführer Rudolf Otto, guard

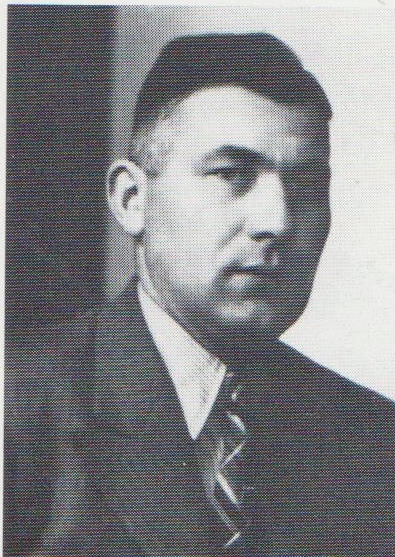

Albert Plate

SS-Sturmscharführer Albert Plate, deputy commandant; killed in action on October 4, 1944 with the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division “Prinz Eugen”

Johannes Runge

SS-Hauptscharführer Johannes Runge, forest camp, built crematoria ovens; believed to have died of his wounds after being captured by the Soviets in February 1945 at Poznań, Poland

SS-Hauptscharführer Erwin (Erich) Schmidt, canteen & provisions; believed killed in action in February 1945 at Poznań, Poland

(Police) Wilhelm Schulte, guard; born June 23, 1912; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 13 months in prison; sentence dropped on appeal

SS-Unterscharführer Max Sommer, victim valuables; died in Bonn prior to trial

(Police) Alexander Steinke, guard; acquitted at trial in 1963

Franz Walter, gas van driver

Toni Wornshofer, truck driver

(March 19, 1944-January 18, 1945)

SS-Hauptsturmführer & Kriminalkommissar Hans Bothmann, commandant; born November 11, 1911 in Dithmarschen, Germany; arrested by the British on April 4, 1946; hanged himself the same day

SS-Hauptscharführer Erwin Bürstinger, motor pool; born February 16, 1908 in Wels, Austria; fate unknown

Ernst Burmeister

Polizeileutnant Ernst “Max” Burmeister, commanded police detachment; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 3 ½ years in prison

SS-Unterscharführer Walter Burmeister, commandant’s driver; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 13 years in prison

SS-Hauptscharführer Hermann Gielow, gas van driver; born October 9, 1892 in Berlin; tried in Poland; received death sentence; executed at Poznań, Poland on June 6, 1951

SS-Hauptscharführer Wilhelm Görlich, administration; taken prisoner by the Soviets in February 1945; sentenced to 25 years in prison; released in 1949

Revierleutnant Alois Häfele, supervisor of Jewish labor; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 15 years in prison; sentence reduced to 13 years on appeal

SS-Hauptscharführer Herbert Hiecke-Richter, victim valuables; fate unknown

Polizeioberwachtmeister Bruno Israel, guard; born August 19, 1906 in Łódź; tried in Poland; received death sentence; commuted to life in prison; released from prison December 12, 1958; died in Mindelheim, West Germany on April 17, 1968

SS-Unterscharführer & Polizei-Oberwachtmeister Erich Kretschmer, supervisor crematoria ovens; fate unknown

SS-Hauptscharführer Gustav Laabs, gas van driver; born December 20, 1902; sentenced at trial in 1963 to 15 years in prison; sentence reduced to 13 years on appeal

Polizeimeister Willi Lenz, supervisor forest camp; born in Silesia; ambushed and hanged by last surviving group of Jews on January 18, 1945 at the granary as the Nazis evacuated Chełmno

Walter Piller

SS-Oberscharführer Walter Piller, deputy commandant, drove gas van; born December 14, 1902 in Berlin; tried in Poland; received death sentence; executed on January 19, 1949 in Łódź

Polizeiwachtmeister Rufenach, guard

SS-Hauptscharführer Johannes Runge, forest camp, supervisor crematoria ovens; believed to have died of his wounds after being captured by the Soviets in February 1945 at Poznań, Poland

SS-Sturmscharführer Wilhelm Schmerse, deputy commandant

SS-Hauptscharführer Erwin (Erich) Schmidt, canteen & provisions; believed killed in action in February 1945 at Poznań, Poland

SS-Scharführer Stefan Seidenglanz, driver; fate unknown

Polizeiwachtmeister Arthur Sliwke, guard

SS-Unterscharführer Max Sommer, administration; died in Bonn prior to trial

SS-Hauptscharführer Ernst Thiele, driver; fate unknown

The following individuals are reported to have been at Chełmno, but it is not clear when they served there or what position they held:

Polizeiwachtmeister Bartel

Polizeiwachtmeister Blench

Polizeiunterwachtmeister Bollmann

Polizeioberwachtmeister Daniel

SS-Unterscharführer Walter Filer

Polizeiwachtmeister Moyz Kerzer

Polizeioberwachtmeister Oskar Kraus

Polizeiwachtmeister Friedrich Loscheck

Polizeiwachtmeister Sepp Reissner

Polizeiwachtmeister Anton Reiblinger

SS-Sturmscharführer Albert Richter

Polizeiwachtmeister Erich Rombach

SS-Scharführer Franz Schalling

SS-Rottenführer Wilhelm Sefler